Falling together at bodily thresholds

This text was published together with a selection of drawings in The Catalogue of Failures: Issue 3 (2023), featuring contributions from 15 international artists and practitioners, including illustration, horticulture, drawing, poetry, painting, collage, performance, research and somatic experience. The project aims to generate conversations about success and failure, accepted norms (and the unacceptable), worthiness, and value.

Falling together at bodily thresholds

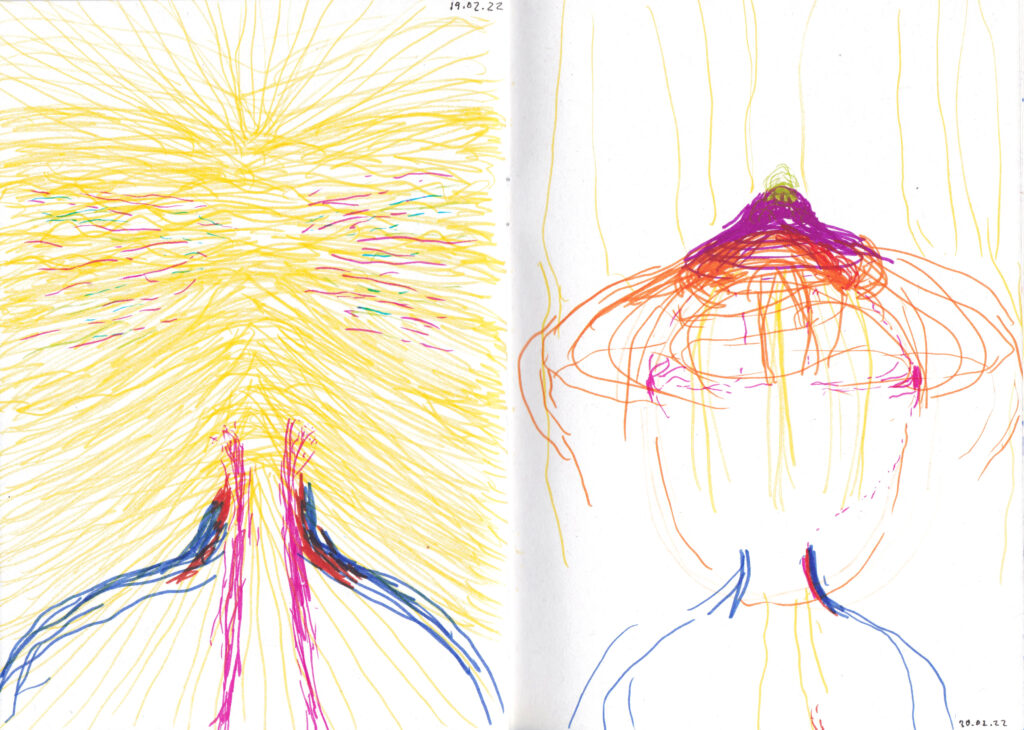

I started drawing my body sensations seven years ago. This has supported me to be more curious and open towards my experiences, including troubling ones. Beginning with the phenomenological qualities of a symptom or sensation, I track and develop an experience further through colour, texture, movement and association. Not aiming to correct or reach a definitive understanding, I explore how to enter and make the experiential information more available to myself.

I began this practice at a time when I was struggling to keep up with studies in an arts educational setting. I felt like a failure, unable to perform. The undermining effects of this on my self-image and social interactions were finding expression in unruly psychosomatic states. When I began drawing these, there was some relief in staying with an unwanted experience rather than trying to suppress it. The drawings formed the basis for a performance at the end of my studies.

I’m on Notebook 32 at the moment. As I’ve continued and learned more about engaging with somatic processes, the drawings have evolved in different ways. Sometimes they register sensory responses to events in the world or in my personal life, states of pleasure or pain. Sometimes they record changing phases of a sickness or a persistent chronic symptom over time. They amplify qualities of a sensation, helping me get in touch with emergent forces within the experience. They depict the nature of the body as a shifting interface of relations and interdependencies.

The word symptom derives from the Greek symptoma – a happening, or an accident, or a disease. Its etymological roots can be traced back to the words syn-, ‘together’, and piptein, ‘to fall’. A symptom might then be understood as a falling together, a coinciding of happenings. In a society ordered by forceful demands for productivity, perfection and individualistic ascension – where falling behind is deemed a personal failing – the need to trouble what is actually dis-ordered feels pressing to me.

When befallen with the inability to go along as ‘normal’, what coinciding physical-cultural- ecological conditions are laid bare? Acknowledging the unequal distribution of harms falling together with some bodies more than others, and taking care not to romanticise the challenges of symptomatic bodily experiences, what information do our bodies hold? Could the failures to maintain a sound state in an unsound society reveal thresholds to errant intelligences?